Nearly three-quarters (74%) of EU citizens believe their country benefited from membership of the bloc, according to a Eurobarometer survey conducted in early 2025, the highest score recorded since the question was first asked in 1983.

Respondents highlighted economic growth (28%) and new job opportunities (26%) as their country’s main gains from EU membership. The data seems to back their assessment.

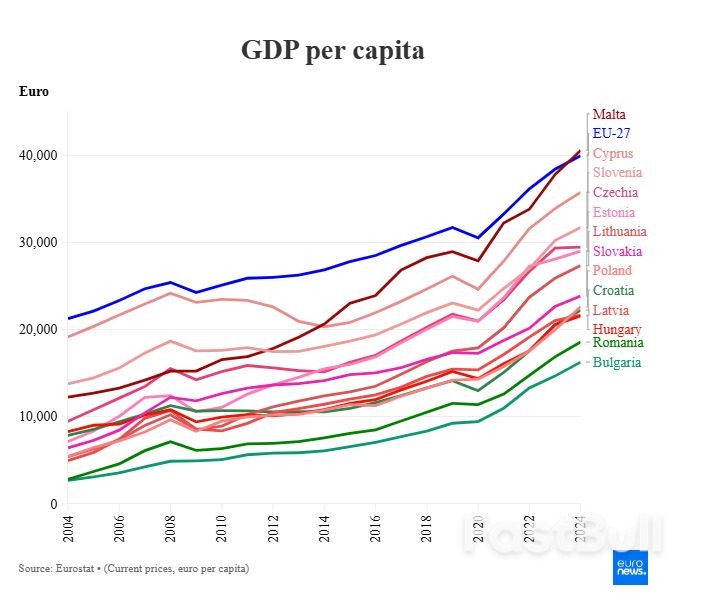

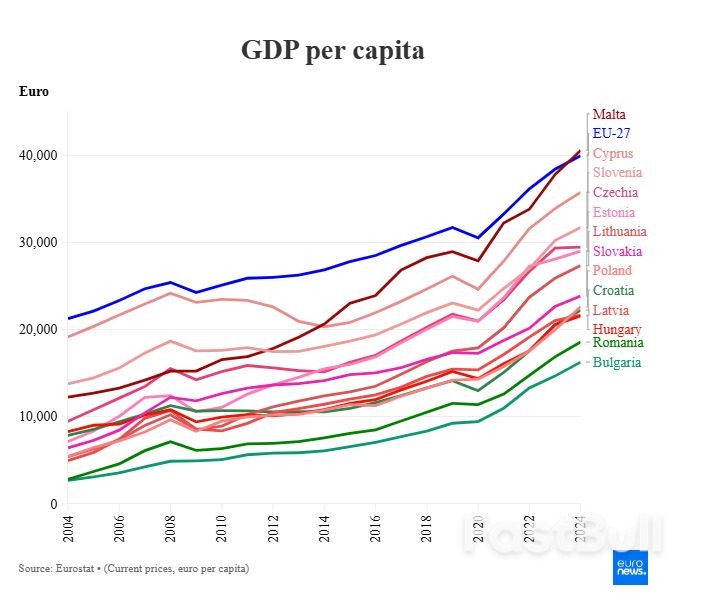

GDP per capita in the Czech Republic went from 45% of the EU average in 2004 to 74% in 2024, jumping from €9,490 to €29,940. In Lithuania, this rose from 26% to 68% over the same period, from €4,960 to €27,350.

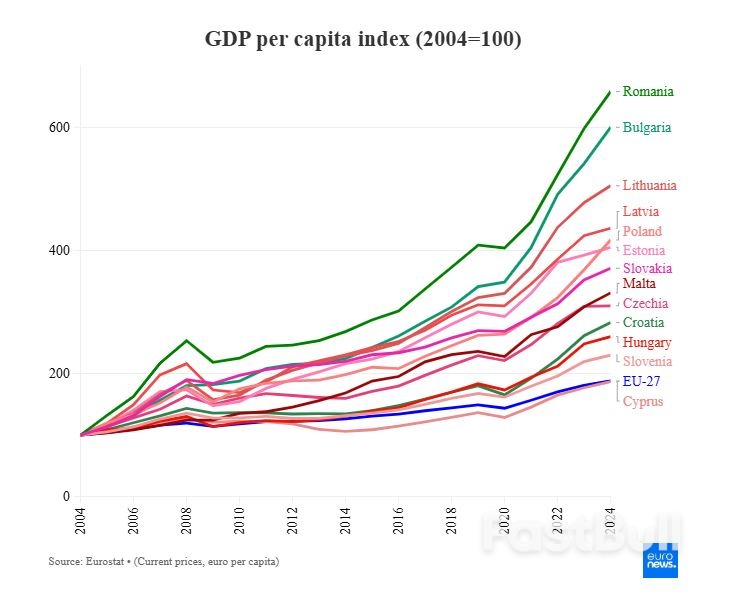

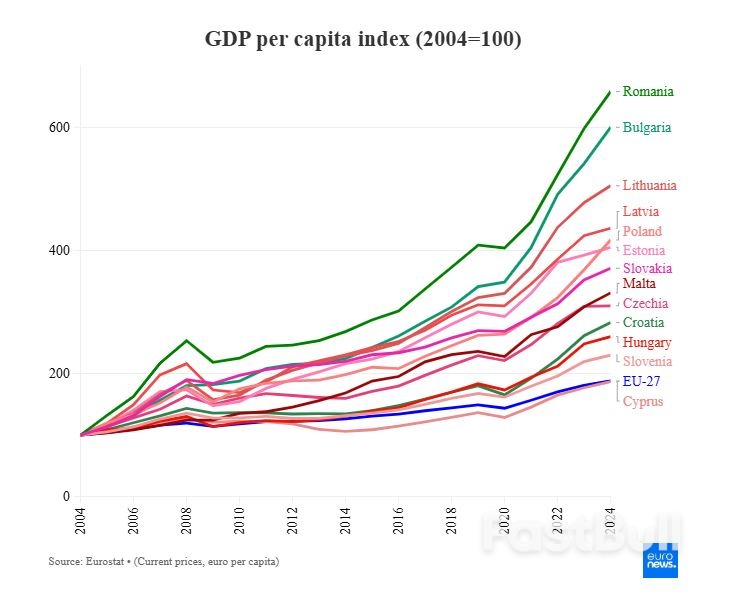

Indexing offers another way to capture the shift. Setting GDP per person in euros at 100 in 2004 for each country allows a clean comparison of how incomes have moved since. A rise to 120 signals that average prosperity is 20% higher than in 2004; a fall to 90 indicates it is 10% lower than that baseline.

Five-fold growth in Romania and Bulgaria

Over the past 20 years, from 2004 to 2024, while GDP per capita in the EU grew by a respectable 88%, with the index rising from 100 to 188 points, growth in the 13 new member states positively boomed. Romania and Bulgaria recorded the strongest growth, of 558% and 500% respectively, and the index reached 600 in both countries.

In this period, GDP per capita in Romania soared from €2,820 to €18,560, and in Bulgaria from €2,710 to €16,260.

There were similarly impressive growth trends recorded in the Baltic states in the last two decades, with GDP per capita rising by 405% in Lithuania, 336% in Latvia and 305% in Estonia.

Surging purchasing power

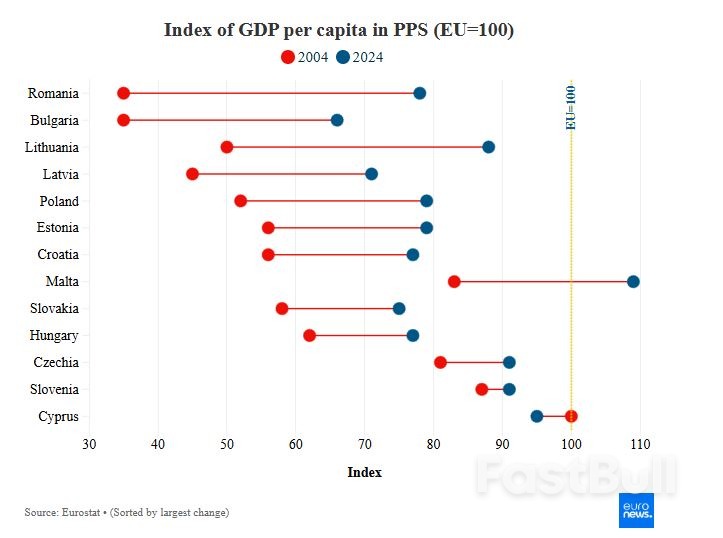

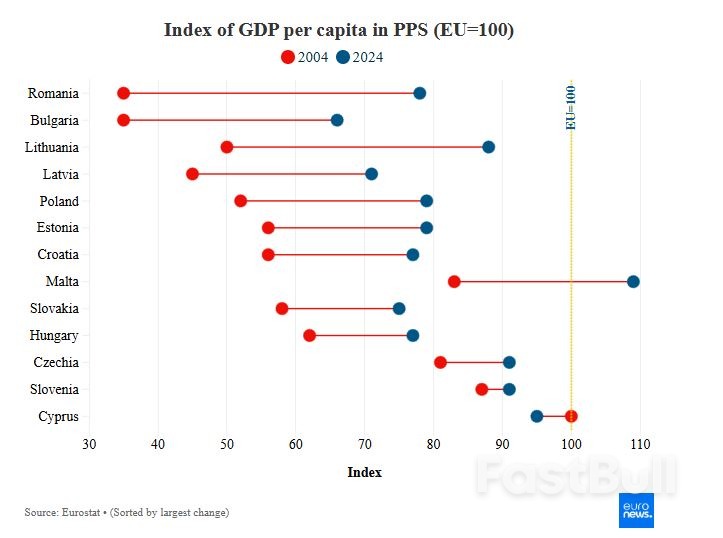

The Purchasing Power Standard (PPS) sheds further light on the economic growth stories of new member states. In theory, one PPS can buy the same amount of goods and services in each country.

GDP per capita in PPS in the EU is indexed at 100. In 2004, Romania and Bulgaria both had the lowest scores of 35 each, or 65% below the EU average. But two decades later, Romania’s purchasing power more than doubled, reaching 78 on the index, while Bulgaria’s went up to 66.

The index rose from 50 to 88 in Lithuania, from 45 to 71 in Latvia, from 52 to 79 in Poland, and from 56 to 79 in Estonia. Any move towards the EU average of 100 means these countries are catching up with the EU standard.

There were more modest increases recorded in Slovenia, rising from 87 to 91, and in the Czech Republic, from 81 to 91 over the same period.

The European Commission insists that the 2004 enlargement “brought a wide range of significant benefits and impressive economic growth to the new members and to the EU as a whole”.

Academic work broadly supports this view. Economist Basile Grassi of Bocconi University finds that accession lifts incomes in new member states without denting those of incumbents. In his words, EU expansion looks rather like a positive-sum game.

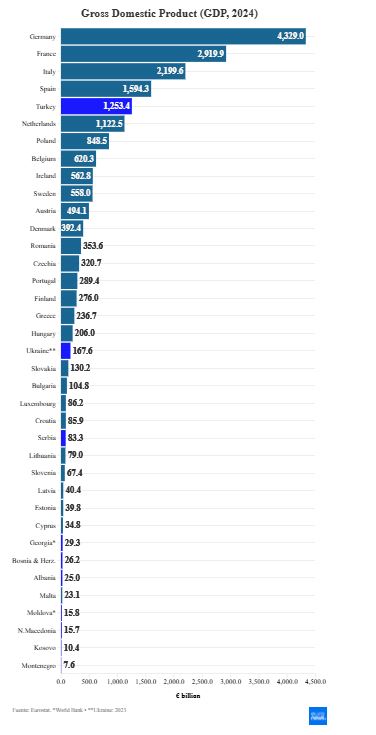

How big are EU candidate countries' economies?

Nine countries are currently formal candidates for EU membership: the Western Balkan countries of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, as well as Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and Turkey, plus one potential candidate, Kosovo.

European Commissioner for Enlargement Marta Kos said in April that a new round of accessions by 2030 is “realistic”, with Ukraine, Moldova, Albania and Montenegro at the head of the queue.

Measured by GDP, most of these economies are relatively small. In 2024 the EU’s output totalled €18 trillion, according to Eurostat.

The 10 countries aspiring to join managed €1.63tr, and Turkey alone made up €1.25tr of that. Take out Turkey, and the nine remaining hopefuls together produced just €381 billion, less than Denmark’s €392bn.

Exclude Turkey, Ukraine and Serbia, and the combined output of the remaining seven drops to a paltry €130bn, smaller than that of roughly two-thirds of existing EU members.

Source: Euronews