Of Turkey And Tariffs

Moderation in the cost of the holiday meal is welcome, but food prices otherwise are on the rise. Tariffs are one of the main reasons why.

We have a crowd of about 30 people coming to Thanksgiving dinner. Feeding all of them will require a lot of preparation, but that may not be our biggest challenge. Finding places for all of them to sit and making sure that certain people sit far away from certain other people is absorbing a great deal of attention. We've had a few food fights on the holiday in the past, and I'd like to spare my carpeting.

The inflated number of guests will contribute to significant inflation in the cost of the meal. Fortunately, the American Farm Bureau Federation estimates that prices for the items on this year's Thanksgiving buffet have declined by 5% since last year. Avian flu has afflicted turkey flocks in the last month, but the frozen birds used by most American cooks have been unaffected.

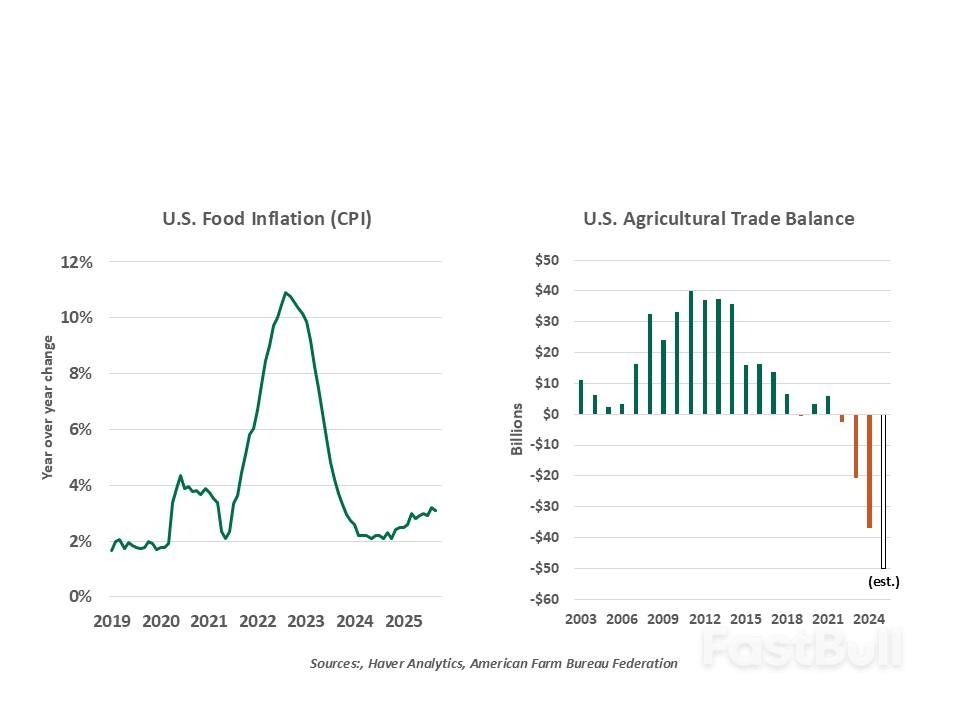

Moderation in the cost of the holiday meal is welcome, but food prices otherwise are on the rise. Tariffs are one of the main reasons why.

The United States is a country of abundance. Its agricultural production ranks third in the world, and it exports twice as much food as any other nation. Nonetheless, the U.S. had a trade deficit in food of almost $32 billion last year, and the shortfall is projected to be even larger this year.

There are several basic reasons for this. While the U.S. has immense surpluses of grains like corn and soybeans, it has deficits for fruits and vegetables. The growing season in the U.S. is limited by climate, so securing year-round availability requires bringing produce in from overseas. Americans also have appetites for foods that cannot easily be grown in the United States. Coffee and bananas are two leading examples.

This year's trade friction has hit the agricultural sector in a number of ways. Foods were not exempt from the across-the-board reciprocal tariffs announced in April; supplemental levies on particular countries followed. This raised the cost of inbound shipments, and prices to U.S. consumers. The Tax Foundation estimates that almost three-quarters of American food imports are being assessed higher import taxes than they were at the start of 2025.

In retaliation for U.S. tariffs, several countries struck back by sanctioning U.S. exports. China once again banned soybean imports in May, replacing them with supply from South America. Canada placed 25% tariffs on all U.S. imports in May, responding to charges imposed by Washington.

This year's trade battles have been particularly hard on agriculture.

These circumstances have produced the unwelcome combination of higher prices for consumers and poor results for farmers. The economic and political ramifications of this have led Washington to change course.

Recent negotiations with China and Canada have resulted in the removal of the most punitive restrictions on agricultural imports. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is considering increasing levels of relief to growers who have struggled to sell their crops.

To improve affordability, the Administration recently dropped tariffs against a range of foodstuffs, including coffee. While households can substitute away from many products when they become more expensive, coffee drinkers are a dedicated lot. The 19% increase in the cost of morning joe over the last year has created considerable discontent.

The policy retreat is a subtle admission that tariffs are, in the main, being paid by households. And while food prices aren't considered in measures of "core" inflation, they have an outsized influence in peoples' perceptions of inflation. Discomfort over the costs of living were a major factor in last year's U.S. elections, and may have contributed to Democratic victories in the handful of races contested early this month. The politics of the pocketbook remain very powerful.