2025's performance is barely believable when you remember how Wall Street started the year, hit head-on by Donald Trump's tariffs. In early April, the S&P 500 even briefly slipped into a bear market (a 20% correction from peak to trough). A few months later, Donald Trump slightly eased the tariffs bill. And above all, US companies kept investing aggressively in artificial intelligence.

All-in

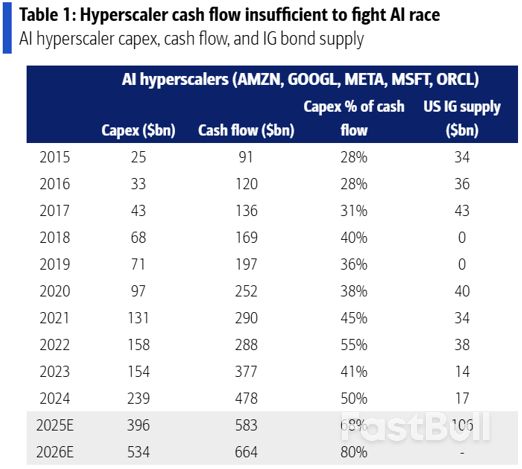

Capex by the five largest hyperscalers (Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft and Oracle) is expected to reach nearly $400 billion in 2025. And that figure is set to rise in the years ahead. The central question now is return on investment.

At this stage, the market seems fairly confident on that front. The cloud businesses of Amazon, Microsoft and Google (the three main players in this market) continue to grow rapidly. In the latest quarter, Azure's growth (Microsoft) was 40%, AWS's 20%, and Google's 32%. Those are striking numbers for companies whose market capitalizations are measured in trillions of dollars.

Despite these growth rates, concerns about return on investment are legitimate. But the hyperscalers keep arguing they need to accelerate, that the main risk is under-investing, and that their main problem is a lack of capacity (data centers, chips…). It all feels a bit like venture-capital logic: you go for it because there is a lot to win at the end, even if some investments do not pay off.

All the more so because these companies remain cash machines. And so the cost of being wrong is not that high. A recent example illustrates this perfectly: the metaverse. It was Facebook's big bet, and the company even renamed itself Meta in late 2021. It was more of a failure because, according to Financial Times calculations, the Reality Labs division would have lost nearly $70 billion cumulatively by the end of 2024. Yet that failed pivot only cost the company 12 to 18 months in the market wilderness. A few quarters in which the stock was dead money (no one wanted it anymore), before the AI train put the company back on track.

Do not forget to return the money

But that last point may no longer be so obvious, and the market has not yet realized it. For about a decade, these stocks have been investor darlings, mainly for two reasons: they are asset light (companies with few physical assets and therefore not burdened by the investments that come with them) and they are cash machines, able to return tens of billions through share buybacks.

But does the AI shift not make that investment thesis obsolete? Because now, hundreds of billions of dollars must be spent to build physical infrastructure, namely data centers. Capital expenditures amortized over several years. But most of the investments are Nvidia chips, consumables that will likely need to be replaced fairly quickly. The hyperscalers believe server lifespans could run up to six years, which is far from obvious.

All of this raises the question of shareholder returns. Will it be possible to roll out large share buyback programs again if the vast majority of cash flows must fund capital expenditures? According to BofA calculations, nearly 70% of hyperscalers' cash flow will be swallowed by capex this year and 80% next year. Over the previous ten years, it was more like 30% to 50%.

In the same boat

These companies therefore now have to turn to debt, which was not the case in the past. At the end of September, Oracle issued $18 billion in bonds; Meta raised $30 billion in late October; Alphabet $25 billion in early November; and Amazon announced in mid-November its intention to raise $15 billion. Nothing dramatic for companies with extremely strong balance sheets, but it is still a sign they need to seek financing elsewhere, that they are no longer able to shoulder all investments on their own.

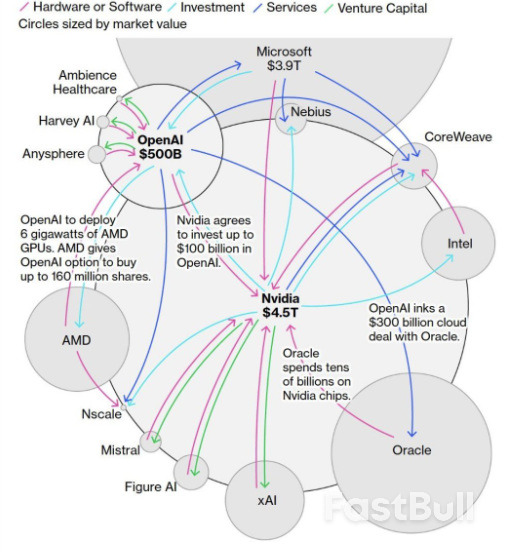

Beyond the amounts to finance and the growing reliance on debt, it is the circular nature of this ecosystem that raises questions: customers financing their suppliers, equity stakes taken in every direction… And in the middle of all that, one player: OpenAI, which is not profitable but whose funding needs are estimated at $1.4 trillion by 2029.

The ecosystem's circularity may be the main risk. Because then, a slowdown at one player can turn into a vicious circle. But for now, the circle is virtuous. One firm's capex becomes another's revenue, and growth is there. Valuations are pricing in a bright future for everyone, and artificial intelligence carried the S&P 500 this year to the doorstep of 7,000 points and the Nasdaq beyond 25,000 points.

A K-shaped economy

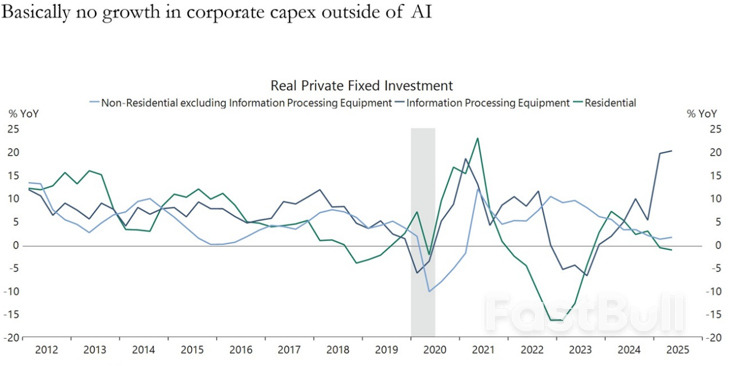

And it is not just Wall Street that is being lifted by artificial intelligence; it is now the main engine of US growth. In the first half of 2025, GDP growth was 1.6%. Growth driven by AI-related investment, whose contribution to growth was 1.4 percentage points in the 1 st quarter and 1.5 points in the second quarter, according to Bank of America estimates.

In short, excluding AI investment, GDP growth is almost zero over the first half. So there are a few sectors buoyed by the AI boom and the rest of the economy is stagnating. A finding confirmed by the data on capital spending.

The AI boom has therefore brought back to life a concept that emerged with the Covid pandemic: the K-shaped economy. An economy in which some sectors rebounded strongly while others kept sinking. Today, while the US economy appears to be holding up well, it is in reality an economy in which AI drives investment and consumption depends mainly on the wealthiest slice.

And the two are linked. The AI boom is driving a surge in equity markets. A surge that translates into an increase in household wealth, especially among the wealthiest, who own the most stocks. And when your wealth rises, you are encouraged to spend more. That is the wealth effect.

This K-shaped economy concept also explains what we see in opinion polls: a majority of Americans dissatisfied with the economic situation. Despite Wall Street records, and despite strong economic growth. GDP in the third quarter rose 4.3% at an annualized rate. But at the same time, the "current economic conditions" component of the Michigan consumer sentiment index hit its lowest level in ten years in December. Because Americans are facing a cooling labor market (meaning more difficulty finding a job and fewer pay rises) and still-high prices. According to Politico, nearly half of Americans (46%) believe the cost of living is the worst they can remember.

Source: marketscreener